As we approach the end of what has been a monumental decade in terms of the way music consumption has shifted, it’s worth taking stock of how our relationship with this great art form has been fundamentally altered by streaming and subscription platforms.

In short, music is overworked and underpaid.

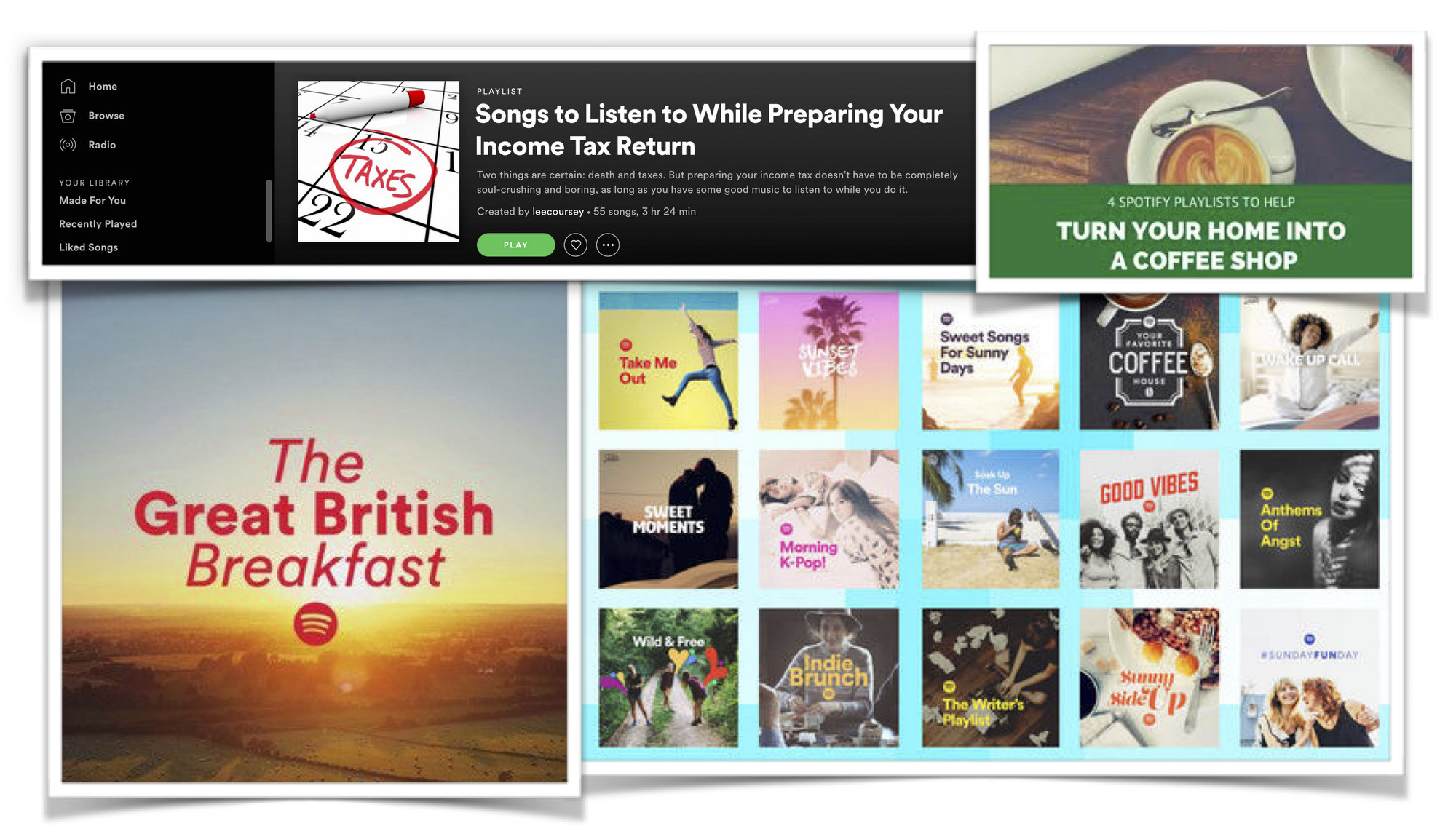

Music is becoming increasingly functional. Simply charged with making the dullest of tasks just vaguely more bearable – as opposed to being something we do or enjoy in its own right

Now more than ever, the way that music is marketed to us as insatiable consumers is for it to be defined by its everyday usefulness to us, in some pseudo-Marie Kondo fashion. We’re told what music is good for. What banal activity it should accompany. Instead of asking ourselves how much does this song affect me?

Playlists are categorised less so by genre and increasingly instead after the moment you’re lead to believe you should listen to them in.

This musical ‘tasking’ – reducing music to a simple functional operation sets a dangerous precedent. Not only does reducing hours of the artist’s blood, sweat and emotional toil to Coffee Morning Concentration feel a bit unedifying – marketing music purely as an aid to facilitate or concentrate on something else entirely, constitutes the thin edge of the wedge for creativity.

Bland, generic music prevails quite because it’s functional

Not because it really moves the listener or pushes the envelope – quite the opposite in fact. It exists in the background attempting not to bother you or connect in any meaningful way (what is known as ‘lean-back’ listening, often associated with algorithmically generated playlists). Great if you’ve got an essay to finish or your VAT return to do.

Labels ask when would fans listen to this? Not would they like it. It’s the 21st Century iteration of their age-old question “would they buy it?” which of course, now largely ceases to exist.

If streaming represents new revenue, it’s only natural that those concerned with the bottom line gravitate towards types of music that can be constantly “on in the background” as that earns more. Dido was once famously described as “music you can microwave pasta to” and she’s sold over 40 million records. Sigh. From AWAL: Behaviour & Algorithmic Playlists:

playlists like Sunday Morning, centred around an activity or a particular time of day can result in plenty of streams but more often than not, the engagement is fairly low

And whilst there is evidence that music played at around 70dB (i.e just loud enough that it stops you over-focussing on the task yet not so loud that you begin to pay attention to the sound), as a musician, starting the songwriting process with half an eye on producing something that should basically be sonic wallpaper, doesn’t represent any kind of future I want to be part of.

As we approach the 2020s, the window of music solely for pure listening pleasure is just simply too niche and non-lucrative. The concept is vanishing. Most ‘listeners’ are allegedly just too busy. As a business model, the industry needs something more insidious.

The music therefore that proliferates, are those songs that don’t ‘ask too many questions’. Artists that don’t colour outside the lines – are comfortable, ruthlessly familiar and easily forgettable. Yawn…

Starting the songwriting process with half an eye on producing something that should basically be sonic wallpaper, doesn’t represent any kind of future I want to be part of

So can music only thrive moving into the next decade if it serves some additional purpose? Does this not devalue and redefine our relationship with the artform more widely? It’s like hanging a Matisse in the downstairs toilet.

Is it time we asked ourselves whether music is simply just the aural Prozac of modern living?

Too Unlimited?

The ubiquity of eat-as-much-as-you-like music right there in your pocket has meant music is often employed as an auditory band-aid, little more than white noise used to drown out the rest of the world – only ever a WhatsApp message or email notification away from being sidelined. It’s less important – happy to be interrupted – by definition, second rate. What AWAL call “music as accessory, not main attraction”.

If we used an analogy of any other kind of relationship – surely if we spent so much time with another person without actually giving them any true attention, it would be likely we’d begin to take that person for granted. Of course, we can’t apply that sort of anthropomorphic personification literally.

But whilst the freedom of being able to access virtually any track instantaneously is undeniably liberating if we’re not mindful of it, the sheer ever-presence of music can undermine our very relationship with it at its core

A recent Nielsen study showed the average US listener listened to music for 32 hours a week. That’s just four hours shy of the hours in an average American working week. We never get the chance to miss or crave music.

Wouldn’t it be strange if it was TV box sets instead of albums that performed this function? Something you put on in the background when doing something else entirely – something purportedly more ‘important’. Netflix begins tagging Stranger Things as Coffee Concentration or Summer Picnic etc – nothing would ever get made.

But that’s music’s shortfall. You don’t have to look at it.

Meaning you can just let it roll in the background. It’s what Niklas Goke calls ‘Compulsive Listening’. The link between a primary task and the sonic collateral is cemented. The task itself is made more tolerable and as such seems elevated. The music is largely peripheral and is de-valued over time. From Niklas Goke: How To Make Music A Useful Part Of Your Life Again

Remember how we struggled to get music into our lives? The iPod changed that. My entire music library in my pocket. The iPhone then made sure I literally had music locked and loaded 24/7. Immediately, the virus awoke. It’s a trend that tears music out of the once meaningful place it had in our lives. We don’t listen to feel, we listen to function.

DIY

Advances in mobile technology have allowed the user the autonomy to curate their own moments on the fly. The opportunity of having a now limitless supply of music always at hand has meant we are able to integrate music into areas of our lives where previously it was impossible (underwater personal music players allow for swimming playlists for example).

The pace of 21st consumption and content obsessive personalities mean we soundtrack everything and playlist names reflect this.

You could argue that these ‘functional’ or ‘moment based’ titles are no different from what home mixtapes were named back in the day (Californian Road Trip; Saturday Night etc). The major difference however being the ability to instantly share said playlist globally (you would’ve had a job getting your cassette out to much more than a few mates or a girl you were trying to impress back in the day).

This visibility of how users are categorising music feeds algorithms and the chicken and egg of producer and consumer begins again. Do the metrics of this new sort of user-based labelling subconsciously constrain which new artists cut through or instead, provide new acts with a clear pathway to appeal to already existing markets? The same way conventions of any genre have been doing for years. Only this time based on their shared past-times, as opposed to any demographic commonalities or a scene per se.

Will the industry more widely allow creativity to be sidelined in preference for new music to appear useful in some capacity?

Forces of economy may dictate which is more important – usefulness or emotional connection.

Form or Function

So are functions the new genres? It’s highly likely we’ll continue to see an increase in the way music is classified defined by its relation to a literal activity or behaviour into the next ten years – a kind of shorthand designed to appeal to the time-poor. A growing intolerance to the shortcomings of one-dimensional labelling and pigeon-holing more broadly in society catalyses this too.

Categorising music has always been a metaphorically semantic endeavour. Music can no more be ‘grunge’ than it can be ‘pink’ – it’s just a semiotic label. As such, labelling music is in itself a somewhat flawed and controversial practice. Resorting to more occasion-based descriptors (in the way that has been done previously with genres like Dance music or Dinner Jazz for example), as opposed to demographic or geographic type descriptors (black music, country music etc), seems in the current politically-correct climate, somewhat inevitable.

Resorting to more occasion-based descriptors as opposed to demographic or geographic type descriptors (black music, country music etc) in the current politically-correct climate seems somewhat inevitable

Music as Instagram Moment

As music becomes overtly functional – associated with often mundane sorts of tasks, we run the risk of never formulating lifelong connections to a track or a band at all. Special songs and artists have always accompanied key milestones in our lives, from the first dance at your wedding to music at your funeral.

There is however a noticeable shift amongst younger audiences especially, towards demanding music provide a quasi-emotional backdrop for scenarios that were once devoid of it.

In the same way the trend to make the visually unremarkable appear glamorous or important on social media perpetuates social media itself, employing songs as a superficial tool to be able to outwardly pertain to be living your best life (throws up in mouth) is clear for all to see.

Not only do we effectively value music less, yet symbiotically we’re asking it to do more in terms of how we present ourselves, and all of the time.

Music’s real value has always been in its escapist ability to deliver a true emotional resonance (at least in part explained by the neural pathways to dopamine it creates). It’s the same reaction we have to good food, drugs or sexual gratification.

If we attempt to somehow bypass this physiological reaction by producing and in turn categorising music that we’re never really intended to love, aren’t we dulling the emotional edges of ourselves altogether? Like only eating food that only fuels us, but doesn’t actually taste half-decent?

Of course, as a musician and a lover of all manner of styles myself, there is nothing necessarily wrong with weaving music into the fabric of your day to day existence. As long as you don’t relegate it to purely functional background fodder in the process. As long as you don’t forget to enjoy it.

To listen to it intently once in a while. To really fall in love with it.

After something with a bit more substance to it? Check out our fortnightly new music playlist Aberrant Aural Wallpaper featuring the choicest authentic undiscovered new music alongside some timeless rare crate dug gems.