Now the pubs in our manor have reopened it’s time to revisit some of those topics that are best discussed passionately over a few jars. One that crops up regularly is this: what factors go into the making of a great record? There’s a lot more to music than notes, frequencies, chords and beats. We need to get another round in and also consider: the artist’s feelings and emotions at the time of recording; the influence of available technology; and the social, cultural and political reference points that may have influenced the songwriting and the production.

There’s another factor that’s easily overlooked: the role of location in the creation of music. In a world that’s digital, global and constantly connected, how does ‘where music is made’ influence ‘how it sounds?’

In 1977 David Bowie was looking to escape the bright lights and hedonism of Los Angeles. He was one of the most famous rock stars on the planet, but he was dealing with addiction, on the brink of nervous collapse and aware that his stage personas – Ziggy Stardust, Major Tom, The Thin White Duke – were in danger of eclipsing his true identity under increasingly extravagant costumes and make-up. He needed escape, stability and reinvention – to come back to himself – and he needed somewhere to make this happen.

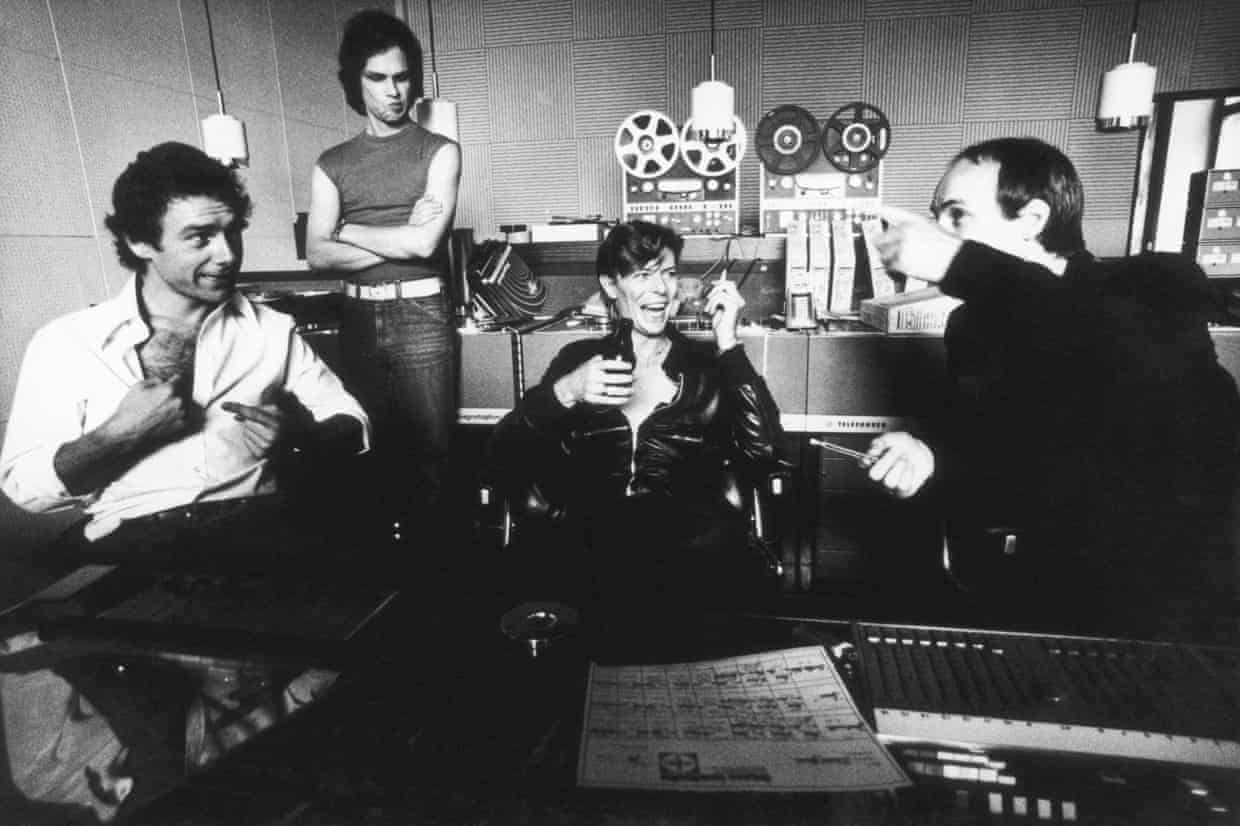

Bowie, producer Tony Visconti and the band took up residence in Hansa Studio in West Berlin, where parts of the previous album ‘Low’ had been recorded. Bowie dressed plainly and enjoyed the locals’ total lack of interest in him (he got up onstage to sing some songs in a nightclub and the audience asked him to sit down so they could enjoy the main act.) The band worked hard and fast in the studio – a former converted concert hall that had been used by Gestapo officers during World War II as a ballroom, and located about 500 yards from the Berlin Wall. Visconti recalled: “Every afternoon I’d sit down at the desk and see three Russian Red Guards looking at us with binoculars, with their Sten guns over their shoulders. That atmosphere was so provocative and so stimulating and so frightening that the band played with so much energy”.

Guitarist on 'Heroes'

Heroes (released in October ’77) was an iconic collection of powerful songs, with critics praising the artist’s growing musical maturity and creative courage. Patti Smith called it a “cryptic product of a higher order of intelligence.” Berlin had been instrumental in Bowie’s journey from addiction to independence; from painted mannequin to an artist without a mask.

Around 2014 something new was happening in South London – the birth of UK drill. “We needed drill” North London producer Bkay told DJ Mag. “Before that, it was pop music, some hip-hop and Afroswing, and it was all good, but it’s not what the hood wanted. We wanted something from the gutter.” Drill had emerged in Chicago somewhere around 2011 as an offshoot to trap. As artists like Chief Keef and Fredo Santana gained recognition, UK artists in South London put their own spin on the genre, with dark atmospherics, the ‘1-2-2’ hi-hat step and woozy sliding bass.

Producers like Carns Hill and MKThePlug played with tempos and mined rich wells of leftfield samples. As we’ll see elsewhere from different times and places, there was local collaboration as the main players looked for freshness and innovation, countering a recurring criticism that plagued its artistic credibility — that its beats and bars sounded “samey”. MKThePlug: “When I started producing in 2015, there was literally one tutorial on YouTube for making drill beats and it wasn’t even up to date,” he says. “Man literally had to fly all around London, linking different producers, to find out how to do it. There wasn’t much to expand on because we were all feeding off each other.”

In 4 years UK Drill became a cultural phenomenon, fuelled by YouTube figures that grew like wildfire; 67, their alumnus R6, and Krept & Kronan clocked up 13, 24 and 20 million views respectively for various releases.

The sound and imagery of UK drill frequently reflected its roots in the streets of South London: violent lyricism, gangs, the wearing of masks, the threat of a knife. There was controversy and wearily predictable outrage in the mainstream conservative media, and perceived imagery in the lyrics provoked censorship. 1011 were ordered to restrict violent lyricism and to notify the police about forthcoming live performances. At the beginning of 2019, Skengdo & AM were given two year suspended sentences for breaking an injunction by performing the track Attempted 1.0 at a London show.

But as UK rap journalist Ciaran Thapar writes, these artists are simply reflecting their reality, truthfully describing the locale in which they exist day to day; where social injustice, poverty, stretched youth services, violence and crime are parts of everyday life. In February 2019 an open letter with 65 signatures from human rights organisations, academics, lawyers and journalists stated: “We call on the Metropolitan police to stop seeking these repressive and counterproductive injunctions. All artists should be afforded the same rights to freedom of speech and creative expression.”

America in the late 1960’s was going through a time of seismic unrest. Civil rights clashes, anger towards the Vietnam war and the draft, political tensions under the Nixon administration and regular outbreaks of violence: the Kent State shootings and the assassination of liberal champion Bobby Kennedy just five years after his elder brother. History shows us that unrest can bring cultural revolution; and a small mountainous neighbourhood behind Los Angeles became the base for an artistic explosion on a par with the Italian Renaissance.

There was a national mood of protest; and that protest formed the basis for a growing counterculture. Musicians descended on LA from all over the USA seeking an outlet for their voices. The quiet tree-lined roads of Laurel Canyon felt more like a home to these artists than the celebrity boulevards in the centre of the city.

The area witnessed an explosion of music that continues to have a huge influence some 50 years later. The Laurel Canyon era rejected corporate America; this wasn’t about churning out pop hits to order in the Brill building, or manufactured bands like The Archies. It was about a songwriter with a borrowed acoustic guitar, strings uncut and curling from the headstock (nobody does that anymore?!), sitting by a fire during a chilly LA night. The sound was intimate, emotive, and introspective; poets and troubadours expressing their feelings, fears and vulnerability. Arrangements came from what lay to hand – guitars and other stringed instruments (e.g Joni’s Appalachian dulcimer), old upright pianos, the harmony voices of roommates; influences ranged from English folk, blues, psychedelia and protest singers like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger.

By the end of the ‘60s the list of Laurel Canyon inhabitants read like a who’s who of American songwriting: Frank Zappa, Crosby Stills Nash and Young, Jim Morrison, Van Dyke Parks, Mama Cass, JD Souther, Richie Furay; the Eagles played poker with Joni Mitchell on Monday nights. Glenn Frey describes living above Jackson Browne and listening to the young songwriter painstakingly constructing Doctor My Eyes in the room below – refining and reworking endlessly until it was right. The music was forged with collaboration: the artists made music together, jamming all night in each other’s houses. They shared lyrics, guitar tunings, partners, ideas, and drugs; added harmonies to each other’s songs; they formed bands and broke up bands, started and ended love affairs.

The geography played a part too. Frey: “There was just something in the air up there. I came from Detroit and things were flat. In the Canyon there’s houses built up on stilts on the hillside and there’s palm trees and yuccas and eucalyptus and vegetation I’d never seen before in my life. It was a little magical hillside canyon.”

The warmth and honesty of the music contrasted with the darkness that accompanied the eventual implosion of the scene: the Manson murders, numerous early deaths (Mama Cass, Danny Whitten, Gram Parsons, Jim Morrison) and too many of the artists drowning in tidal waves of drugs, fame and cash – bitterly at odds with the counterculture that had originally brought them to the Canyon.

But super-producer Rick Rubin, who now owns The Houdini mansion on Laurel Canyon Boulevard says: “Laurel Canyon had the cross-breeding of folk with psychedelic rock, and created some of the greatest music ever made.”

We can look to a colder climate for another example of environment and geography shaping the sounds and songs coming out of a country.

Author and musician R Michael Hendrix describes Iceland “a teenage earth…unsure, curious and filled with potential. It is dynamic, unpredictable, and still in transition. That is its beauty.” In The Geography of Bliss, Eric Weiner says “Icelanders tell me the land itself is a source of creative inspiration and, indirectly, happiness. The ground is, quite literally, shifting beneath their feet. There are, on average, twenty earthquakes a day in Iceland.”

The landscape unquestionably inspires. But the challenge for Icelandic musicians and composers from times past was always how to capture this unique environment with just the palette of acoustic and orchestral instruments available to them. A land of colours and nature – black sand, purple flowers, yellow fields, inky mountains, glaciers and volcanoes – was begging for a new way of making music.

The transformative power of electronic music freed Icelandic composers from all restraints, allowing them to create music that sounded like their country felt: erupting, evolving, constantly changing, rich in texture and atmosphere. Recent years have seen an explosion of experimental pop artists and soundtrack composers coming out of Iceland, many becoming key players in their fields: Olafaur Arnaulds, Jóhann Jóhannsson, Vök, Jófríður Ákadóttir, Högni, Hildur Guðnadóttir, Bjork and Sigur Rós, with founder member Jonsi collaborating recently with composer Carl Michael von Hausswolff on 2020’s Dark Morph, in which field recordings of deep sea creatures and bats become the basis for the songs.

The landscape drives the inspiration for the sounds in the composer’s head; the infinite nature of modern technology allows their creation

So you’re a label boss and you need a pop hit for your artist. Go to Sweden. Proportionately to its size, this country of 10 million people exports more pop hits than any other country in the world, with Swedish songwriters and producers regularly dominating the The Billboard Hot 100.

Producer and songwriter Max Martin has the third-most number-one singles on the chart, behind only Paul McCartney (32) and John Lennon (26). In addition, he has the second-most Hot 100 number-one singles as a producer, 22, behind George Martin. Along with his collaborators like Rami Yacoub, Per Magnussen and Andreas Carlsson he’s produced hits for Backstreet Boys, Britney Spears, Pink Usher, Avril Lavigne, Jesse J, Katy Perry, Christina Aguilera, Taylor Swift and The Weeknd – to name just a small few. That’s quite a CV.

What is it about Sweden that makes it so successful in the pop industry?

You could point to the beauty of the natural environment or the charms of Stockholm for creative inspiration. But in this instance we need to dig a bit deeper; by taking a look at social cultural influences that prevail in Swedish society, and how they drive the creative process.

Swedish society is built on equality and collaboration. “Swedish organisations are known to have what we call a ‘flat decision-making structure’ where everybody participates equally, whether you are the boss or not. I think for song-writing, that type of social model turned out to be very useful.” (Dr Ola Johannson, Professor of Geography at the University of Pittsburgh).

In Sweden, there is no ‘Mr or Sir.’ There’s the King, and there’s everyone else.

The heartbeat of Max Martin’s early success was Cheiron Studios, where every step of the songwriting process was based on teamwork and collaboration. Jörgen Elofsson, who worked alongside Denniz PoP and Max explains: “We weren’t really alone doing anything. We sat around and critiqued each other a lot. There was this vibe of helping each other, which was kind of unique at that time, I think.” The set up of the studios was conducive to collaboration. Jörgen describes how songwriters would constantly run into one another. To reach the vocal booth they’d have to pass another studio, which they’d often pop into en route so that they could listen to each other’s work (modesty forbids, but that’s just like The Futz Butler studios….)

Compare and contrast that to a Laurel Canyon songwriter sitting by the fire with an acoustic guitar. These days a modern pop hit will likely involve a team of songwriters, a vocal producer, synth and beat programmers, and mix and mastering engineers (not to mention the artist themselves.)

Creative collaboration has been described by thought leader Matt Ridley as ‘Ideas Having Sex.’ That is, the recombination and reshuffling of genes giving you a result you haven’t had before. Alongside his pop projects, Max Martin has worked with Johan “Shellback” Schuster from Sweden’s hardcore and death metal scene and Bonnie McKee, a classically trained pianist and choral singer. His knack for a tune is undeniable – but it’s the culturally-driven philosophy of collaboration from his home country that arguably gives him and his compatriots the edge.

For our last example, we’re going to stretch the boundaries of our subject a little. But hey it’s nearly closing time…

How do you make a record in your childhood bedroom that reaches the whole world? By understanding how they’re listening to it.

In 2017 Apple sold 15 million Airpods. By 2019 that figure was at 60 million. It’s fair to say that Airpods had become the tools of choice for listening to music, especially for the younger generation on the move.

In his parent’s house in Highland Park, LA, a young man was making a record in his bedroom using the most basic of set-ups: a cheap mini keyboard, a computer with standard effects plug-ins, an old upright piano. “My parents are super-artistic. But we grew up pretty much broke.“ His life in music started with his Dad showing him how to play a pop tune on the piano. “This is fun, even though I’m not really good at it yet — but I could get really good at it.” It showed me that it can be fun to do something you’re bad at, and learn how to become good at it.”

The young man was Finneas O’Connell and he was making a record that would come out under his sister’s name: When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? by Billie Eilish.

The sound of the record went against the grain of a lot of other contemporary radio productions – sparse atmospheric arrangements (the hit Bad Guy uses just one synth), random foley effects taken from their live sessions, and barely-whispered vocals. When Mix engineer Rob Kinelski first listened to the tracks he was shocked and exhilarated by the sound; bass-heavy, with minimal high frequencies and relatively little in the mid-range, virtually no reverb, lots of weird and wonderful incidental sounds (striking a match, a squeaking door), and those hushed vocals. In addition, the use of space and silence: gaps of two or three seconds with nothing happening at all. Brave and refreshing in a world constantly craving attention and begging you not to skip.

“Everything was deliberate. There’s a song on the album with an off-centre kick drum. I made the kick mono because I thought it sounded cool, but then a little later they said, ‘you know what? Let’s put it back to where it was. Another day I added some ambient reverb to a part – the only note on the mix was ‘let’s lose the reverb.’”

The record was a perfect collision of two locations: a young man making a record in his bedroom on the simplest of set-ups; for the rest of the world, out in the street, listening on their Airpods. How better to experience those silences; the absence of reverb and high end frequencies; the random sound effects; the huge bass, with the kick panned left; those whispered vocals, a friend confiding in your ear?

When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? went multi-platinum in 20 countries and Finneas’ little sister Billie went supernova. A proper family result.

We’ll leave the last word to Finneas, as he’s now known – true success comes when you can drop your surname – and how the creation of his music was influenced by the world around him:

“This is a dark time in the world, and there are lots of political issues in the United States. We want to make sure we reflect the times we live in in our art. If we just made really positive and happy music, it would be very tone-deaf.”