We’re delighted to have sign off on our first project of 2024 – a new TVC campaign for Sainsbury’s.

Supervised by Leland Music, we were commissioned to produce a re-recording of The Jam’s 1980 number one Start! indistinguishable from the original master. Why? The client loved the track but found the lyrics unsuitable and distracting throughout the spot, but record label Polydor realised no instrumental version was ever produced from the original master tapes.

Our challenge was to intricately and 100% faithfully reproduce an identical version of the song – just without the vocals. Our version needed to be so impossible to tell apart from the original recording that the client could cut back and forth between our mix and the original master seamlessly without the audience knowing.

This would be no small feat. Not only matching the playing nuances exactly of Paul Weller (guitars), Bruce Foxton (bass) and Rick Buckler (drums / perc) but as importantly – nailing the engineering, production and mix work of Vic Coppersmith-Heaven.

As we always say – there or thereabouts is nowhere near. This needed to be note-perfect.

This would be fun…

A.I no go

There are lots of new pieces of A.I software that attempt to remove vocals from a master – leaving just the instrumental (or vice versa) and believe me, some are like magic. Great for remixes. But, they’re definitely not perfect – most leave noticeable artifacts behind where the singing once was – ghostly trails of reverb or missed consonants the algorithm just can’t deal with.

These apps are a great tool and the tech will only improve, but it was clear that currently A.I wouldn’t cut it here – the renders produced across a number of programs just weren’t of sufficient quality, even sat underneath VO and sfx.

Getting cracking

As a Mod in a former life (that’s another story), this is a track I knew reasonably well. My first task was to work out the basic harmony (the chords) and structure (verse chorus etc) which I did in about ten minutes by ear.

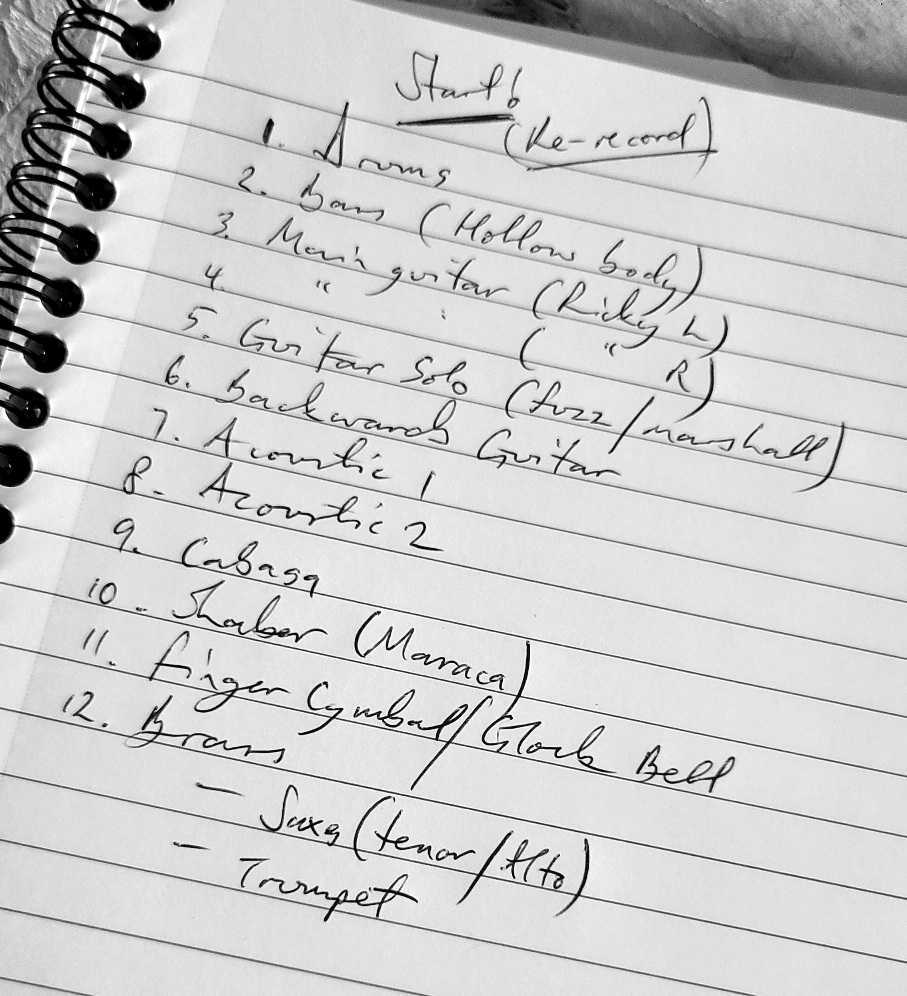

Building on this I then listened critically to the arrangement to draw up a list of all instruments on the master, including those magic layers and double tracks that aren’t always eminently obvious on first listen (but would definitely be noticeable by their absence (e.g cabasa, acoustic guitars and brass).

It was then a case of meticulously working out and understanding each of these parts in intensive granular detail.

This included extensive research of what equipment the band were using both live and in the studio at that point, the studio it was recorded in (RAK), the size of the live room, the mixing desk it would’ve been tracked through, the mics likely used on that session, right the way down to the width of the tape recorded to and the gauge of the guitar strings.

Projects that require this level of authenticity and precision are often the sum of 1,001 tiny considered choices. Get even one wrong and it throws the whole thing off

We then looked at what was being played specifically ‘under the microscope’. Where on the neck and which specific chord fingering was Weller playing? What area of each drum did Buckler strike the skin? What pickup on the bass was Bruce Foxton using and what thickness plectrum created that sound best? What the A.I was useful for was separating the individual instruments out a little better. It wasn’t by any means perfect, but having a passable stem for each of the parts – drums especially, made understanding the fine details and re-recording the parts verbatim just marginally less of a challenge.

Laying down the kit

We started with the drums. Using software, we were able to create a note perfect click track that learned the natural tempo ebb and flow of the original to the millisecond. Following this unique tempo map, where Buckler sped up, we would also and where he sat back we would too.

We settled on a Pearl kit with open transparent heads, tuned as closely as we could to the record. We laid down a handful of takes being sure to match the energy and volume of each hit relative to the other drums in the kit as meticulously as possible.

All about that Bass

Owing more than a little to the Beatles’ Taxman bassline, recording the bass was a more straightforward endeavour. The bass really drives the track and is unusually upfront in the mix. Matching Foxton’s feel didn’t pose too many headaches. Foxton was famous for his growling Rickenbacker 4001 basslines or his flubby, woody tones of a Gibson hollow body bass. For this session, he was certainly playing the latter. So we called into action our 1966 Gbson EB2, with a 2mm pick and drove an API 3232 preamp (the same kind that would have been used at RAK at that time) hard into breakup distortion to get that perfect saturated forward bass sound the song is so famous for.

Nice.

Guitars

Despite being a power trio, this song has a deceptive number of guitar layers. Weller’s main studio guitar around the time of the Sound Affects album was his iconic Pop Art USA Rickenbacker 330. He also made use of a cherry red mid-sixties Gibson SG and occasionally an Ovation acoustic too. Knowing this gave us a solid starting point to recreate his tone.

From archive footage we found, playing Start! live Weller preferred an SG into a Marshall stack. But in the studio the tone is unmistakably the Rickenbacker and through a more chimey amp – likely a VOX.

The only ‘Ricky’ we had was a 12 string 360 (a beaut all the same). Doing some investigation, we managed to track down a hire company God’s Own Guitars in Peckham, who had a 1984 Rickenbacker 330 that could be hired by the day that would be perfect for the job.

Giving the performance a suitable amount of punk energy and imperfection we double tracked the main guitar part, panned hard left and right through a nice tube VOX amp.

We now had the backbone of the song starting to take shape. We layered on the other parts including the guitar solo and backwards guitars, brass and acoustics and we were ready for the all important mix.

Mixing

Whilst we’d taken every possible step to get as close to the original sound by getting it right at source, it was clear that the mix would be crucial to the viability of our instrumental master.

The key thing here, was not to mix it in a way that would make it sound best given all the available technology we have 45 years on, but instead to make it sound one hundred percent authentic to the era

The drum mix is surprisingly dry (minimal echo or reverb) for example, whilst the guitars despite feeling very in your face and spiky, in reality lack any great initial transient attack (often a result of recording to tape). This was very much a case of mix to what you hear – not what you think you hear.

With the performances in the bag, detailed EQ, compression and dynamics work was painstakingly undertaken over a period of a couple of days to get everything sounding truly identical.

If you like it, you better put a ring on it…

One element of the mix that proved very tricky was the snare drum sound. The snare is fantastically punchy yet has a very clear ringing overtone to it that makes it quite unique. Whilst the live performance we recorded had nailed the body and overall tone of the snare drum, the ringy nature wasn’t quite there yet.

This called for some unorthodox creative thinking…

We pulled out another snare from our collection and tuned it as closely as we could to the pitch of the original recording (we found that vari-speeding – slowing the playback speed of the recording session, allowed us to further get closer to the exact tonality of the pesky ring).

As we already had the snare drum hits recorded, it would be no good simply hitting the drum or overdubbing it. We needed a way to create the ring without any initial stick sound.

I had an idea…

I solo’d the snare drum performance we already had recorded and ran it out of the computer and into a bass amp. The signal was low pass filtered (to cut out the high frequencies) and then boosted with a sub bass enhancer plug in to bring out the bottom end.

The bass amp was then laid flat on its back with the speaker pointing upwards and the newly tuned snare sat on top of the grill with some light muffling to stop it rattling.

Now each time the previously recorded snare was hit it would create a very short low note in the bass amp, which because of the pitch, would heavily vibrate the snare sat on top enough to cause it to ring.

A mic was then positioned to capture this ringing and the whole take from start to finish recorded.

The newly created ring was then slotted into the mix (after a highpass filter to remove the low sub note). A bit of EQ, sidechaining and transient design to control the length of the ringing and hey presto, the combined snare sounded bang on! Jobs a good’un.

The track was mastered through a tasteful set of outboard gear with one final pass of EQ matching to the original.

The spot features cameos from Kevin McCloud and voiceover courtesy of Stephen Fry. The ad went live on January 6th. Here’s the full re-record.